By Alexis Davis Millar (January 26, 2020)

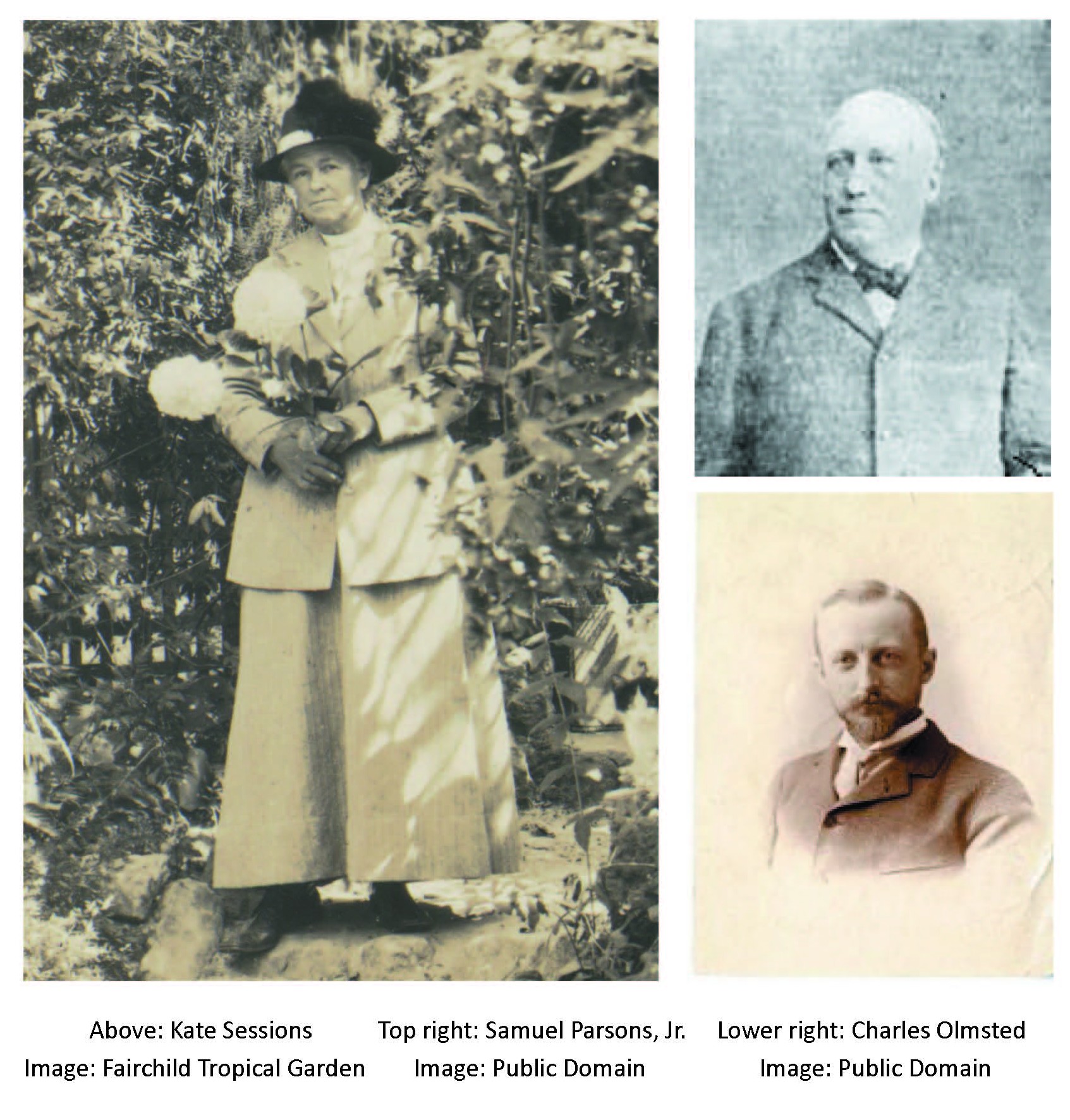

For over 150 years, Balboa Park has shone as an ever-changing gem of San Diego. The 1,400 acres was originally set aside for public recreation in 1845, a portion of which would become Balboa Park. Officially designated a public park in 1868, its master plan evolved in the early 1900s by landscape architect Samuel Parsons, Jr. With the 1911 pivotal decision to celebrate the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in Balboa Park, competing renovation plans for the park would forever set the tone for all that would follow.

Water feature in Alcazar Garden (Credit: Alexis Davis Millar, 2019)

John Charles Olmsted and local horticulturalist Kate Sessions’ regionally sensitive planting design and site planning design, which prioritized capturing views, local land, and views of the bay, would be rejected in favor of architect Bertram Goodhue’s central mesa siting of the primary exposition space. Fulfilling this siting premise, Frank P. Allen, Jr. and Paul G. Thiene then created a planting design with turf and spectacular exotics. Allen and Thiene’s dazzling design choices, hailed as a huge success and captivating many visitors to San Diego, informed our definition of garden beauty in California – lush year-round, high-maintenance flower beds, and high water-dependence. Political might and funding pushed forward the central mesa siting and lush design, with Olmsted resigning from the project over these differences in long-term vision for the park. Along with Olmsted’s resignation, the design also lost the local expertise of Kate Sessions, as her role as consultant to Olmsted dissolved.

Twenty years later in preparation for the 1935 California Pacific International Exposition, architect Richard S. Requa expanded the building design and vernacular landscape style to include Moorish influences and styles relevant to the contextual architectural history of the Southwest. Throughout the design, he judiciously used water features as accents. Still preserved today was a key feature of his landscape design, that of transforming the formal garden to become the Alcazar Garden. The Alcazar Garden, with its Moorish tiled water features, was reconstructed in 1935, true to Requa’s design.

The guiding principle in Requa’s planting design for Balboa Park was one of green textures with colorful islands, leaving much of the park largely undeveloped. Though Requa ultimately considered his design unsuccessful, he was proud of a space he created for a specifically California native plant garden in the park.

The decades that followed the Exposition brought additional buildings, garden additions, and uses. Of the original 1,400-acre park created in 1868, 200 acres have now been lost. During the WWII era, for example, as a continuing resource for the local community, the park buildings also served as adjunct U.S. Navy buildings for the Balboa Navy hospital. Renovations during the 1990s included the Japanese Friendship Garden near the Spreckels Organ Pavilion.

As Balboa Park’s design continued to evolve into the late 1980s, local landscape architecture firm Estrada Land Planning produced a Park Master Plan and continues to re-envision how the park’s visitors can best experience the museums and outdoor spaces. Guiding the master plan by Estrada Land Planning and Civitas landscape architecture is that the core design is returned to the main plaza in an essentially vehicle-free zone while providing universal access to the museum buildings and landscape spaces. The community context and voices have been vigorously considered in the process.

Credit: Estrada Land Planning and Civitas, Plan for Plaza de Panama, May 2012

The Plaza de Panama Project concept, shown above has generated much passionate conversation. To stroll the Plaza unencumbered by the ever-dominating vehicular traffic was perceived as the next chapter in the evolution of this Park.

As illustrated in this very recent San Diego Union-Tribune article, the dynamic discussion continues to this moment, as to what is most appropriate in the next evolution of this community treasure.

Perhaps even the planting design of historic contributors such as Samuel Parsons, Jr., Kate Sessions, and John Charles Olmsted will also be reconsidered in this water-conscious time.

A special thank you to Nancy Carol Carter and Vicki Estrada for providing me such valuable Balboa Park materials in preparing this post.